Gardening with Manzanita

Last year, my blog concentrated on the seasonal care of a native plant garden. This year I’ll describe some of the plants that I think belong in the garden.

In the midst of winter, Manzanita dominates my attention as dormant buds looking like chicken feet sprout from the ends of branches. They actually started growing several months before. Depending on the species and elevation, some Manzanitas bloom as early as late December. Our foothill manzanita (Arctostaphylos viscida ssp. viscida, known as Whiteleaf Manzanita) blooms in February to April. It is one of our earliest spring-blooming bushe and grows in full sun to light shade.

A wide variety of Manzanitas are native to California, each species in its own geographic location of coastal areas, chaparral, the foothills or the mountains. The plants may be tree-like, large shrubs, small shrubs or groundcovers. The Greek meaning of Arctostaphylos is “bear berry.” Manzanitas belong to the Ericaceae or Heath family.

Manzanita has small pendant urn-shaped blossoms that are usually white but may be blushed with pink. Bees, butterflies and hummingbirds are attracted to them. Bumblebees and solitary bees often use a “buzz technique” to shake the pollen free, rapidly moving their wings to vibrate the blossom. Honeybees may slit the side of the blossom to reach inside for the nectar. Butterflies and hummingbirds have long enough tongues to reach right into the flower opening.

Manzanitas need very little attention in your garden. Most Manzanitas are drought tolerant, accepting occasional water but no standing water. Water plants during their first year in your garden, but limit the water to once a month or less as the plants become established. The soil needs to drain well and must be acidic or neutral, not alkaline. Manzanitas prefer sun, although some do well in partial shade. Provide good air circulation by planting them apart from other plants and allowing space for their mature size. Do not fertilize, for Manzanitas don’t like rich soil.

Although Manzanitas do not have to be pruned, you may want to pinch the tips of branches after the blossoms fade, thus encouraging branching below the flower cluster. You may also want to remove lower branches to reveal more of the smooth, sculptural deep red bark. Be sure to cut back to the collar on the main stem or to a strong side-shoot of the branch, avoiding stubs of bare wood that will fail to sprout and will ultimately die. Pruning is best done during the summer when cuts will dry and heal quickly and before dormant buds form. Plants are most easily propagated by cuttings or layering rather than by seed.

While the Manzanita that grows natively in your area is a safe choice for your garden, others may also thrive. Horticulturists have developed particularly lovely plants into cultivars that are offered for sale in retail nurseries and native plant sales.

Emerald Carpet is one of the most widely-grown groundcover. Tolerant of average garden water but not alkaline soil, a small plant will spread widely in a few years. I am growing it successfully on a north-facing bank with limited sunlight. As a specimen shrub with striking deep pink blossoms in early February, a large ‘Sentinel’ Manzanita grows on top of a mound in the Master Gardener Demonstration Garden in Grass Valley (located on the NID property at 1036 West Main Street). Last year it was pruned significantly to reveal the attractive bark. “Louis Edmunds” is another eye-catching pink-flowering shrub. Both of these have thrived in my native plant garden for five years.

Sometimes Manzanitas suffer from fungus that causes dieback of branches. They can also have bacterial leaf spot, wood borers or aphid galls (which make red blisters on the leaves but aren’t really a problem.). In your garden, avoid overhead water, remove dead branches (be sure to sterilize the pruners between cuts) and dispose fallen leaves if you suspect disease.

Manzanita has two interesting environmental adaptations. Many manzanitas have a burl at ground-level and they will sprout again from this burl after wildfire. The foothill Whiteleaf Manzanita does not have a burl, but the heat of fire and the resulting charcoal help its seeds sprout. Manzanita leaves have adapted to the heat of summer by growing vertically to minimize the surface exposed to the sun, thus conserving moisture in the leathery waxy leaf.

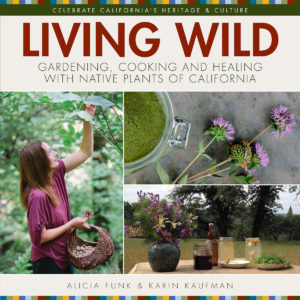

Manzanita means “little apple” in Spanish, a reference to the appearance of the 1/3-inch fruit. Wild animals and birds eat the berries and you can too. Living Wild provides easy-to-follow recipes for manzanita sugar, muffins, and cider. With lovely blossoms, unusual bark and intriguing food value, Manzanita is an important addition to your garden.

-Darlene Ward

4 comments on “Gardening with Manzanita”

Comments are closed.

I’m so glad you wrote about Manzanita in the garden. It is one of my favorite plants and I find it beautiful year-round, but many people are turned off to it due to the belief that it is a fire hazard. In my area, Manzanita has been blooming for about a month now at the lower elevations. I first noticed white blossoms, but pink blossoms are opening on some of the plants now. I can’t decide which I like better. Aaron Sims, rare plant botanist for CNPS, told me his mom calls Manzanita “Refrigerator Trees” because their branches always feel cold.

I’m headed out to my garden to check the branches right now. Of course, it was in the 30s last night, so they will probably feel cold! We also call the madrone tree a “refrigerator tree” because its bark feels cold, even in summer. Since both madrone and manzanita are in the same family, it’s reasonable that they would share the characteristic. Thanks for your comments.

Can you believe I spotted Manzanita blooming on a hike yesterday? January 18th must be a record. I first smelled something deliciously sweet and looked around until I spotted the pink blossoms.

Early blooming seems to be related to both elevation and amount of sun. I have noticed some blossoms opening at 2200 elevation. Thanks for mentioning the fragrance. I didn’t mention it because it has never been that obvious to me, even though I know it is supposed to be fragrant. I’ll get closer and check it out this year.